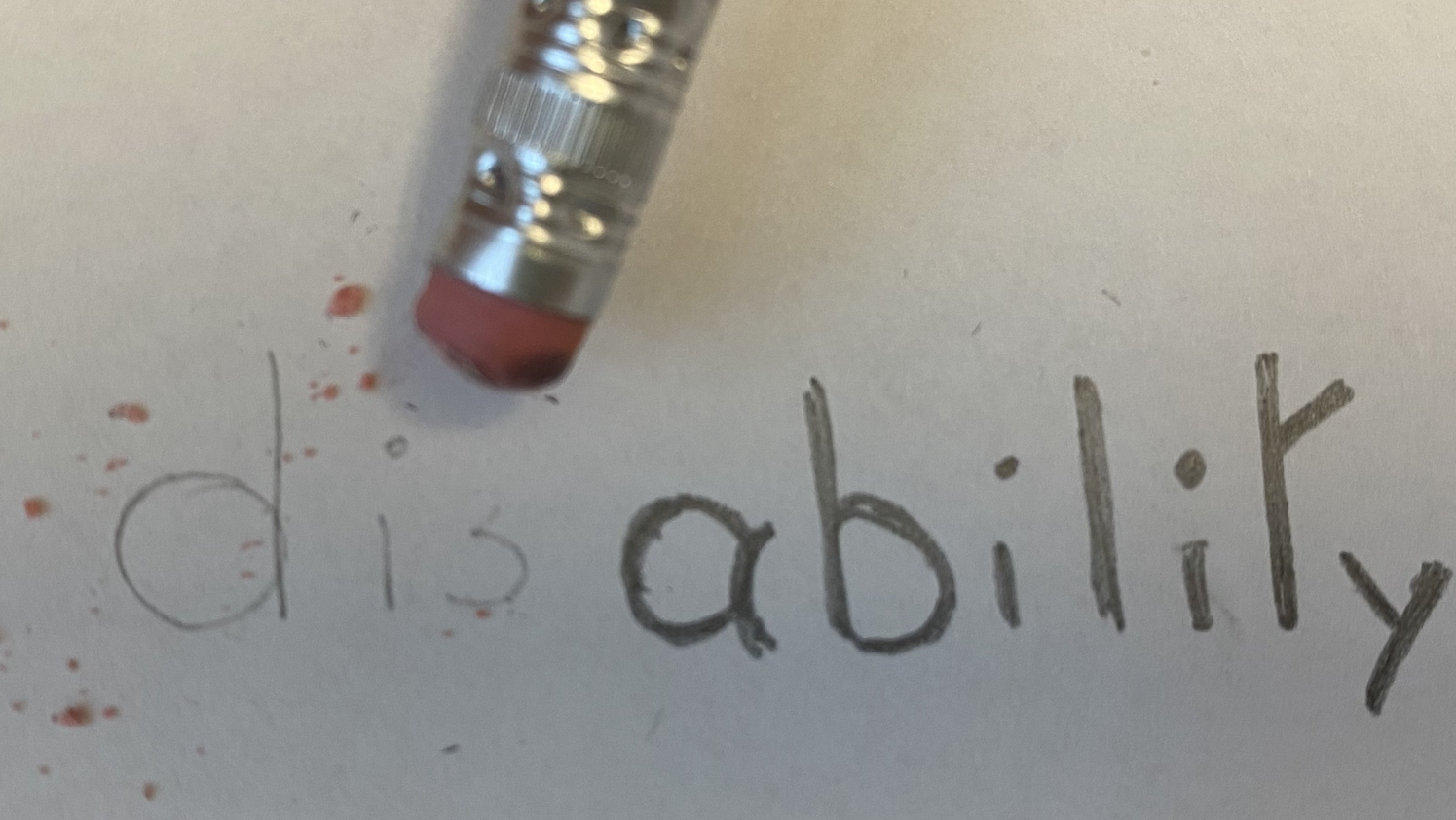

As a deaf scientist growing up and working in different countries across the world, I have experienced different environments, each with their own set of challenges. But I have noticed a clear transformation in my self-esteem, confidence, and ability to succeed in pursuing my dream career after coming to America for graduate school. Based on my experience, various societies around the world have differing degrees of unconscious bias, which contribute significantly to their explicit commitment to disability equity, and hence influence opportunities of STEM training to hoh/deaf people. Atop the general challenges mentioned in my previous blog post, unequal global distribution of people’s unconscious biases and stereotypes against us complicate worldwide efforts to making the global STEM climate more inclusive to hoh/deaf people.

A person’s “microenvironment” - their immediate support network consisting of their family, friends, teachers etc) - greatly impacts their psychological, social, mental well-being, professional development as well as personal growth. My experience studying in the United States showed me that the successful implementation of legislation like the American Disability Act (ADA) in 1990, combined with active advocacy against unconscious biases create a welcoming and accessible climate in which people with disabilities can thrive. Prior to coming to study at the University of California Davis (UCD) in America, my pursuit of STEM education had been harsh. I hope that sharing my experiences can highlight the need for improving and equalizing global accessibility to STEM education.

Unequal global distribution of people’s unconscious biases and stereotypes against us complicate worldwide efforts to making the global STEM climate more inclusive to hoh/deaf people.

During my first visit to the student disability center at UCD, the director told me that I would be provided with real-time captioning to accommodate for my hearing difficulty. Real-time captioning provides you with a real-time feed of every word the professor says on your computer monitor during class, and is a major improvement compared to notes obtained from classmates. Before this visit, I had never thought that learning in classes could be simple and enjoyable. But the major revelation of my visit was the existence of several deaf medical students at UCD, and the realization that these accommodations not only supported their medical training, but also gave them the opportunity to excel. Realizing that hoh/deaf individuals can actually become physicians - or anything they want for that matter - unleashed the positive power of self-actualization in my mind and helped me overcome the stereotype threat that I was suffering from. Stereotype threat is a conditional predicament that describes the fear of confirming a negative stereotype that exists about one’s group. Before UCD, I was never provided with any pragmatic accommodations in elementary school, high school, or college. While teachers did volunteer their time to help me, I couldn’t follow their every word and struggled to understand what they were trying to explain. To keep up, I needed to spend most time after class reading reference books, attempting to grasp as many concepts taught in class as possible. I also actively contacted lecturers for course materials in advance of classes to self-learn and prepare questions for them after lectures. To maintain good grades for more opportunities in schools, I avoided classes I was interested in, and instead took classes I knew I could excel in. Though I maintained an excellent academic track record, I was lost in the dilemma of following my interest or keeping good grades for future career opportunities.

Thanks to the support of a trained, certified real-time captionist team, and the inspiring words from the director of the student disability center, my learning experience at UCD has been one of the best of my life. Here, I no longer stayed in my “academic comfort zone”, and I started taking classes ranging from astronomy, entomology to geology, solely based on my interest. Inspired by the existence of deaf medical students in UCD, I became more confident with my hearing loss and gradually lifted the stereotype threat I suffered from. In ten months, I not only fed my curiosity of understanding our Universe through a wide variety of classes, but also boosted my confidence by still maintaining an impressive academic record. Learning had never been easier. For the first time in my life, I was able to have a wonderful study-life balance with outdoor adventures almost every weekend. My journey at UCD allowed me to experience a normal life, all due to the accommodations made for accessible STEM education. This experience made me become more comfortable about my hearing loss and my deaf identity and gave me the confidence to pursue my dreams.

The leaders from academia and industries in STEM field should be educated for unconscious bias and stereotype threat. They should also actively recruit more qualified students with special needs to their schools.

My experience showed me that the extent of unconscious bias against hoh/deaf people really depends on where you grow up, which in turn leads to disproportionate access to education depending on where you live and study. In some parts of the world, hoh/deaf people are considered “disabled” and medically “abnormal”, while they are considered a “linguistic and cultural minority” in others. Since some societies view hoh/deaf individuals as inferior and “abnormal”, solving learning accessibility issues of hoh/deaf individuals becomes a low priority matter that receives scarce resources. Therefore, the stereotypization of hoh/deaf people in the dominant hearing world not only affects how they are treated in their specific social environments, but it also has a powerful influence on how deaf individuals view themselves and their deaf peers through stereotype threat.

Many countries have a long path ahead to improve hoh/deaf people’s accessibility to STEM education and to the job market. Clearly, it will require a lot of effort and work to transform the uneven distribution of unconscious bias toward hoh/deaf people around the globe, but I would like to suggest a few steps for action.

First, the leaders from academia and industries in STEM field should be educated for unconscious bias and stereotype threat. They should also actively recruit more qualified students with special needs (e.g. deaf, blind) to their schools. These steps would give a powerful signal to hearing students that hoh/deaf students are not incapable, but merely have different educational needs. However, for countries that do not have an ADA-like act, and that do not sufficiently fund initiatives to provide accessible education, it becomes extremely challenging to provide adequate accommodations to students with disabilities. When I tried to bring change to my home university based on my experiences in the US, my suggestions were met by steep financial barriers that could not be overcome. Therefore, these changes will not be possible without the allocation of an explicit financial governmental budget to incentivize and support accommodations and accept qualified hoh/deaf students and employees.

I recommend that universities require all members of the school to participate in a series of diversity and inclusion workshops. By doing so, hearing people can be made aware of their own unconscious biases and can learn to overcome them.

Second, since unconscious bias and stereotype can easily cross boundaries, students, university staff and professors could bring the prejudice from their home countries to wherever they move, and they may not be aware of their unconscious bias against students with hearing loss. In order to ensure that hoh/deaf STEM students receive equal opportunities to accessible STEM education, I recommend that universities require all members of the school to participate in a series of diversity and inclusion workshops. By doing so, hearing people can be made aware of their own unconscious biases and can learn to overcome them. This small step will represent a big leap forward to a more inclusive STEM environment for everyone.

Unconscious bias strongly impacts the opportunities for deaf people to become successful scientists. By recognizing the needs of the hoh/deaf community, providing governmental fund initiatives for accommodations, and offering opportunities to accessible STEM education as well as to STEM careers through implementing ADA-like acts, we can gradually reform the global STEM climate to become more inclusive to people with various special education needs.

About the author: Lok Ming (Tom) Tam is a toxicologist and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Rochester, where he investigates mechanisms of aging. He is passionate about advancing public health and societal wellbeing. Connect with Tom on Twitter.

Cover Image by Nele Haelterman

We welcome comments, questions and feedback. Please contact us at ecrlife [dot] editors [at] gmail [dot] com.

Would you like to share your own story, insight or opinion? Pitch us here.

Follow us on Twitter to stay up to speed with our latest blog post releases.