Like so many others, we faced a huge dilemma at the end of our respective PhD programs: after many long years of working in the lab: where do we go next? To another lab for a postdoc? Or perhaps, pivot towards industry? At some point, we each took two different directions: Elisenda joined a public-private research institute as a Scientific Manager, while Natalia ventured into entrepreneurship. We first met at Avengers for Better Science, a 5-day event dedicated to topics such as inclusivity, self-care, and mentoring in science where we had an opportunity to share our personal experiences. We discussed the similarities and differences between different post-PhD career tracks, and drafted a landscape summarizing the main options.

Most PhD graduates do not spend enough time researching career options that deviate from the traditional academic career path. Even when trying to expand on their possibilities, PhDs often deliberate potential jobs by comparing their skills or expertise with the requirements listed in the job offer and conclude that they are not a good match. There are other factors beyond your skill set that play a big role in the overall satisfaction of your professional life, such as your role within a team or job security. For instance, both of us have skills in data science. Would our satisfaction differ depending on whether we choose to work for a government, a corporation, or a startup? Most likely, yes! And the optimal choice very much depends on our personality traits.

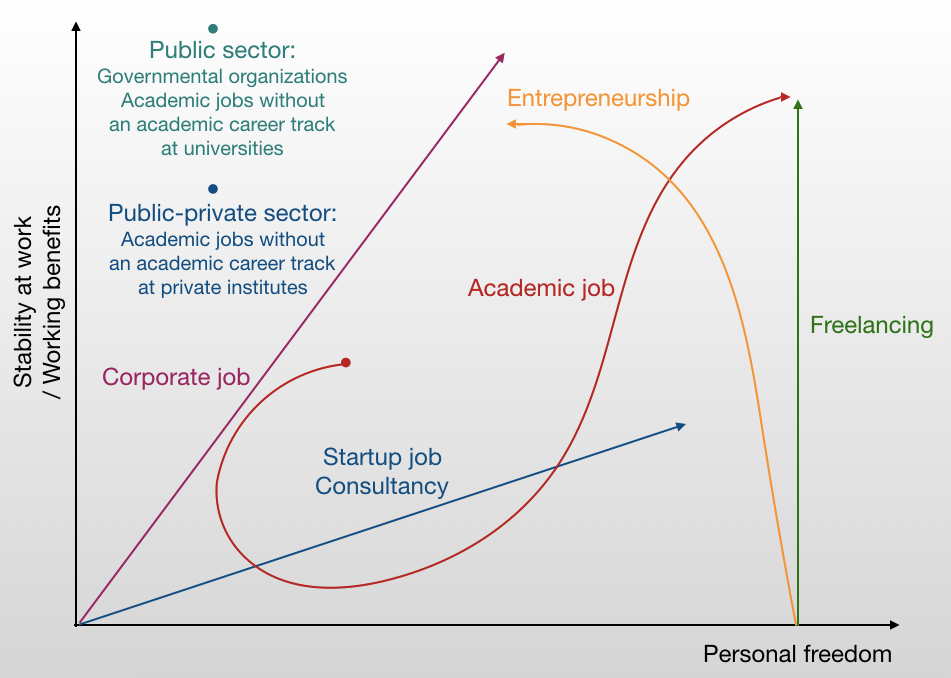

So, how does the landscape of post-PhD career tracks look like, given these personal values? The job market is huge and complex, but we attempted to grasp the essence of it in one picture using two dimensions: personal freedom versus stability (or safety) at work. By personal freedom, we mean an ability to define your projects, choose your team members, and define your own long-term career goals. By stability, we mean decent income (relative to your needs), continuity of income, and good working benefits.

The holy grail of the job market is at the intersection of achieving a high amount of personal freedom, while at the same time, maintaining a comfortable, stable life without worrying about tomorrow. We listed a few of the main classes of post-PhD career trajectories and compared how these trajectories look in our two-dimensional space.

In academia, the trajectory can be a rollercoaster — especially if you work in a very competitive field. You start from a 3-6 year PhD contract which gives you a certain amount of freedom and stability. But then, you need to go through the turbulent a.k.a. “postdoc phase”: short contracts, severe competition, intense grant writing, student supervision, promoting your research, etc. This is when for most academics, the quality of professional life drops the most (although there are exceptions!). For Elisenda, this rollercoaster stemmed from the nature of the public-private institute she worked for, which is partially dependent on external funding from private companies. In this environment, postdoctoral contracts are typically very short, and the amount of insecurity is even higher than when you have a university postdoc contract.

When you enroll on a tenure track, you slowly gravitate towards the happy corner: a stable job with lots of personal freedom. This is a generalization of course — there are branches of science in which the growth towards this happy corner is almost linear, as there is enough space for almost anyone who is willing to develop an academic career. However, in life sciences, severe competition presses on postdocs to take on a lot of (more or less risky) projects, and substantially lowers their job satisfaction. The situation also varies between countries; in some countries, PhD candidates receive fellowships rather than employment, and do not enjoy the same working benefits and stability as postdocs.

Many PhDs switch careers to the public sector: government-funded institutions and jobs within academia that are not on a tenure track (such as, grant writing, teaching, policy, managing a lab, PhD advisor jobs, or scientific communication). In the public sector, jobs are generally stable: you might be able to settle in one place for the rest of your professional career, and the working benefits are usually very attractive. This kind of job can also be found in the private sector (i.e., in private research institutes, which do not guarantee high stability). However, this often comes at a cost of personal freedom: you typically have a well-defined function, deliverables, superiors to report to, and relatively little space to propose new initiatives.

The private sector is also increasingly welcoming to PhDs: researchers are often preferred in the Research & Development (R&D) departments in large companies. Corporate jobs can secure more job stability and working benefits, while gaining valuable work experience. At the same time, promotions to management positions can help increase your personal freedom, for instance through opportunities to propose and lead new projects. PhDs also quickly adapt to the startup culture. In startups, there is more personal freedom by definition, but at the same time, attaining work stability can take much longer than in corporations.

Many PhDs also successfully start freelance careers: as consultants, coaches, data scientists, or software developers. In freelancing, the amount of personal freedom is very high: you have no boss and no one else depends on you. You can also choose where you want to work from and when. Work stability starts at very low levels but increases gradually along with developing your brand, acquiring a base of returning clients, and increasing your income and savings.

Lastly, many PhDs launch startups and become entrepreneurs. Some (but not all startups) stem from academic research, or from problems experienced during an academic career. This largely drove Natalia’s motivation to start her own company, at a point when she felt drained from a futile job search after her PhD and found others were experiencing the same roadblocks. In the summer of 2019, she gave a workshop about post-PhD career tracks at the Organization for Human Brain Mapping annual meeting in Rome; the room was packed with people willing to sit on the floor or stand outside the room just to listen in on the session. Shortly after, Natalia marched into the Chamber of Commerce and registered a company, Welcome Solutions, right after coming back to the Netherlands. The company aims at helping researchers in self-discovery and in finding new avenues in industry, by offering intensive career workshops and creating new recruitment solutions adapted to hiring highly qualified professionals who value non-material aspects of their jobs.

Entrepreneurship gives very little sense of stability at first: around 50% of startups fail within the first few years (still much better odds than to become a PI!). At the same time, the amount of personal freedom is very high: you can define your projects, develop these projects from scratch, and decide whom to work with. While the startup develops and matures, your level of stability gradually increases - but this happens at the cost of personal freedom, as together with the growth of the startup, the number of stakeholders and corporate procedures within the company will increase.

In sum, post-PhD career trajectories differ in terms of qualities they provide. Take into account that this is just a simple 2D-representation of the job landscape while in reality, jobs have many more aspects to them. Within the most important ones, there are the core competencies that make you unique on the job market. Our advice is to think big: take a helicopter view of the job market, and make steps towards a career that will give you a lifestyle compatible with your personality. If you do what you love, the way you love, it gives you the best chance of developing a fulfilling professional career.

Natalia Bielczyk is the Chairperson of Stichting Solaris Onderzoek en Ontwikkeling, a foundation that helps early career researchers in developing their careers within and outside academia by offering free online consultancy. She also owns Welcome Solutions 1, a company that offers career workshops for researchers who consider switching careers to industry, and tests new recruitment models for PhDs and other highly qualified professionals. Twitter: @nbielczyk_neuro

Elisenda Bonet-Carne is a Scientific Manager at BCNatal Fetal Medicine Research Center and a mentor at Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. She is a former telecommunication engineer, with a Master in Neuroscience and a PhD in Biomedicine. She has strong translational experience developing medical software and organising scientific (and non-scientific) events. Twitter: @bonetcarne