In academia, we are used to exploring unknown waters, learning new things, and then sharing our findings and experiences with the world through written communication. When I finalized my interview season for tenure-track faculty positions, a few months ago, I felt an urge to reflect on my experience of the job market by writing about what I had learned in the previous six months. Here are those thoughts.

Many articles exist about the academic job market, how to best prepare for different phases of the interview process, and what defines a competitive applicant. If you are preparing to enter the academic job market and are looking for guidance, you should read those. This is by no means a comprehensive overview of the process. Instead, it is a list of things I wish I knew despite reading a bunch of these articles and attending many seminars and workshops about the academic job market.

There is no universal recipe for a successful application, as all applicants, departments, search committees, and universities are different. This blog is highly biased on my n=1 experience. I am a Caucasian woman, married without children. I was asked about my marital status and the “moveability” of my husband at nearly all on-site interviews, and about children during half of them.

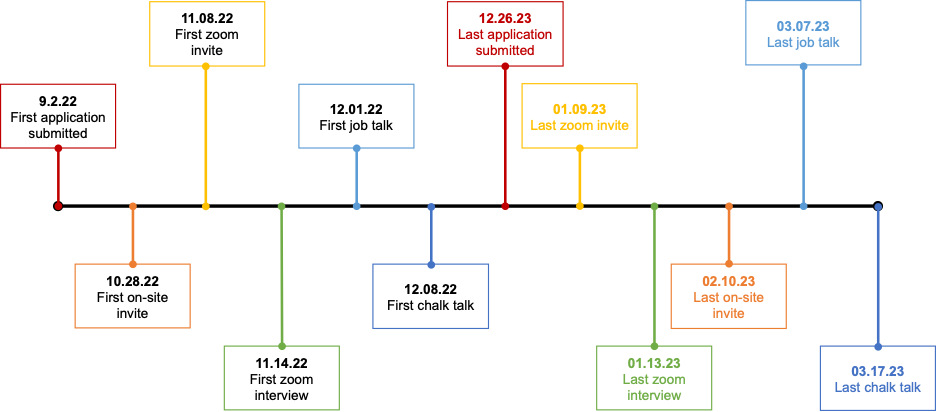

I applied for one round, in the “job market season” of 2022-2023, as a fourth-year post-doc. At the time I submitted my application, I had a postdoctoral fellowship (Dystonia Medical Research Foundation) and a K99 (NIH/NINDS) that was likely to be (but not officially) funded. During my postdoc, I had published, four first author research papers (eLife, J. Phys, iScience, Dystonia), four co-author research papers (Nature Comms, eLife, J. Neuro, Cerebellum), three first-author book chapters/reviews, and I had one first author paper that was under review (Nature Comms).

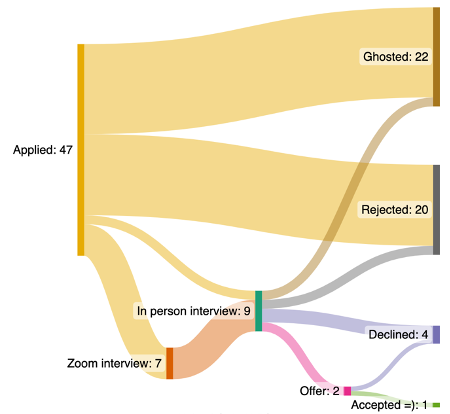

I applied to nearly fifty positions and received invitations for in person interviews at nine departments (Figure 1). These included two medical schools and seven R1 undergraduate institutions (three neuroscience departments and four broad biology departments), four in state, two in city, and five out of state. These are the things I have learned through that interview season:

1. Always be one step ahead of the game.

One of the craziest things of the faculty job search is the hurry-up-and-wait dynamics of the timelines. There was a lot of waiting. Waiting for ads to get posted, waiting for interview invitations, and waiting to hear about decisions and offers. But when you get notified about proceeding to the next round, you can have as little as a week (or sometimes even less) to prepare for your zoom interviews, job or chalk talk, or negotiations.

My advice would be to prepare your job documents in spring. These include:

- a research statement (3 pages)

- a teaching statement (1 page)

- a diversity statement (1 page)

- a cover letter

- your CV

Having these documents ready to go would be a good start, but keep in mind that nearly every application will ask for a slightly different documents. Get examples, these are different from any other document you’ve ever written and they are not a grant. Have as many people as you can read your application package. These documents need to still be crystal clear for tired search committee members who may be reading your application at 9 PM after a glass of wine.

When you finalize your statements, start preparing your job and chalk talks, and for the standard zoom interview questions. Zoom interview questions are highly universal and you can practice answering them in advance. Prepare before you get your first interview invite.

Once you are ready for your interviews, start collecting quotes for your startup. You want to know which equipment you need to run your lab successfully, and you should know how much they cost now (not five years ago).

You will not jinx anything by preparing in advance. You will unlikely get to choose the order of your job applications or interviews, and you won’t be able to practice on the go – you may just have one shot to prepare for an interview for your dream job, with just one week's notice.

2. Build your community.

Find a group of post-docs who are on the job market this year. Whether virtually or at your university. You’ll have so many questions along the way and it will be nice to have people to ask them. You want to find people who are on the job market and in the same boat as you are now. They will have the most accurate information and help. Things change incredibly fast, and people forget even faster.

3. YOU are getting your interviews.

I believed at first that the academic job market was highly rigged, and that people only get interviews at universities where they or their PIs know someone. I was wrong. I wasn’t invited to interview at any universities my PI (or thesis advisor) reached out to. More so, there was no clear connection between my thesis/post-doc advisor and the department I was interviewing at for nearly all places I interviewed at. Of course, it helps if your PI is known as a kind and smart or famous person, but in my experience, it is neither necessary nor sufficient. I found that search committees really do read your application. Do not count yourself out if you feel like a position may be a stretch or because you do not personally know anyone at the university.

To put this in perspective. Searches are usually conducted by a search committee consisting of four to eight people. These people have to agree on who they want to invite for the interviews. Each person on the search committee may be putting their own “friend” forward, but they will still have to convince their fellow search committee members about the qualifications of this applicant. It may be as easy for a search committee to agree on a strong applicant with interesting ideas who they have not met before as to convince the other committee members “their friend” is the best candidate.

4. Fit is real (and pretty vague)

Ultimately, whether you’ll get the interview or the job offer (or not) will all depend on “fit.” I hate the word “fit”. Mostly because it does not fully describe what is meant with it. I think a better word to use is “resonate.” Does your research program resonate with ongoing research? Do people understand your ideas without you having to finish your sentence? Does the department have the same values as you? In other words, do you + your research + department > you + your research at any department anywhere? If the answer clearly is yes, that’s when there is a good fit.

I am a developmental, systems neuroscientist who studies the cerebellum and movement disorders. Ultimately, my two offers came from specific developmental neuroscience searches. These are logical fits based on the job description. However, I interviewed for two other neurodevelopment positions that were clearly not good fits during the interview. Then, there were universities that I thought were a good fit, where I got so disappointed during the visit. On the flip side, I also had multiple interviews that were just phenomenal when I didn’t expect it. Fit is so much more than a research topic.

5. Apply broadly.

You may not know what you are looking for until you’ve seen it. Prior to applying, I thought I wanted to work in a medical school or research institute because it was the environment I knew from my graduate and post-graduate work. But over the course of my interview season, I realized that the atmosphere at undergraduate universities is much different and may fit (ugh sorry) me a bit better (partly because I love to teach). Ultimately, I accepted a position that is a hybrid of both, with my lab in a research institute and my faculty appointment at a university where I’ll be teaching two classes a year. This specific type of position might be rare (and I didn’t even know they existed). You may also not know what you’re looking for until you’ve seen it.

On the flip side, I have not found any pattern in the types of departments that did or didn’t extend interview invitations. I got some big surprise interviews, and some big surprise rejections. There is no magic formula; you’re betting against the odds, so apply to all places you may like to increase your chances of finding the best match!

6. But do not apply too broadly.

I was absolutely baffled to learn how many searches fail, despite most job postings receiving over a hundred and sometimes multiple hundreds of applications. Some of these searches fail because the same pool of applicants are invited at many universities. But some also fail because people decide at the last minute they would never move to X, not even for a dream job. Don’t apply to the places you know you’ll never move to. It’s okay to exclude searches based on geographical locations or personal reasons. Be kind, don’t waste anyone’s time.

7. Once you’re on-site, you’re the one asking the questions.

Preparing for my first interview, I practiced answers for all kinds of standard interview questions, like “describe a time you navigated a difficult conflict” and “what do you think are your biggest strengths and weaknesses.” How many times do you think I had to use these answers? A grand total of zero. You’ll be lucky if the people you meet with have read your research statement or have seen your talks, maybe they have one or two questions about your research. After that, you’re doing the questioning. Ask people about the department culture, students, service or teaching responsibilities, city, their research, etc. Have questions on hand. You’ll be asking a lot of them.

8. Saying interviewing is a full-time job is an understatement.

Between submitting applications, preparing for interviews, being on interviews, traveling to interviews, agonizing about interviews, etc, I don’t think I had an entire productive week in the lab between August and March. During the four months of interviewing, I gained about five pounds because of weird eating and sleeping habits, little energy or time to work out between interviews, and just sheer stress. Make sure you and your boss are prepared for a huge dip in your work productivity. About a million people told me this would be the case and I still underestimated the time and energy it would take me.

Keep this in mind when you are asking for your preferences, meals, and travel itinerary. Communicate your dietary restrictions and ask for sufficient bio- and coffee breaks. Organize travel schedules that work for you. I regret not asking to either drive or bus to some of my closer interviews, and I loved being able to bike to my in-town interviews. For several interviews, I was able to stay an extra night so that I could explore cities I did not know yet. This made a huge difference when making my final decision. Communicating your needs and wants do not make you “difficult” but instead allow you to be the best possible interviewee!

9. Be financially ready.

Okay, this is a yucky one to write about, but it was something I really had not prepared for. For a few of my on-site interviews, I was expected to pay for my own flights (I got reimbursed later, thankfully) and I paid upfront for nearly all transport to and from airports. These costs can add up. Having a little buffer in your bank account will help cover some unexpected charges before you get reimbursed, which can sometimes take quite long.

10. Every chalk talk is different, but they all provide great insight into the department culture

Job talks are pretty much similar between all departments (but you can include at a slide tailored to the department, it’s appreciated). Chalk talks, however, are different everywhere you go. I have done 60- and 90-minute chalk talks, based on one, two, or three projects, being interrupted a million or close to zero times, on a ginormous white board or a small one that flips over, at the same day of the seminar talk or the day after the seminar talk or during a separate visit, and for two interviews I did not do a chalk talk at all. I did all my chalk talks on white boards without slides, but I’ve heard this can differ too. Ask the search chair or your host what is expected in their department and prepare accordingly.

I found some comfort in bringing my own white board markers. I brought them initially because I wanted to be sure the markers would work, but they also provided some familiarity in the different situations and environments. It’s the little things that can give you a bit of a confidence boost.

Ask the search chair or your host what is expected in their department and prepare accordingly.

Not knowing what to expect from chalk talks, I was terrified of them at first. You really can’t fully prepare for them, as you don’t know what the questions will be or what direction the discussion will go into. But here’s the flip side to that: it’s the best time of your entire interview to see how people in the department interact with each other in a professional setting. Do people chat and make jokes just before the chalk talk (good sign!)? Do people let each other finish their sentences (good sign!)? Are postdocs invited to join the chalk talk (good sign!)? Do many people in the department show up (good sign!)? Do many different (junior vs senior, male vs female) faculty ask questions during the chalk talk (good sign!)? Do people help you or other faculty clarify points when there is a bit of confusion (good sign!)? By looking for these signs, I usually had a pretty good idea about whether I would like working in the department after the chalk talk. And while scary at first, they ultimately became my favorite part of the interviews.

11. You won’t hear back from most places.

But like, never. Sometimes not even after finishing the full interview. Not even if you reach out. Ghosting is real. It helps to follow the Future PI Slack Google Sheet to know whether universities have sent out invitations. But this sheet can also be a big source of stress – proceed with caution.

12. Timelines may get mucky, stick to yours.

At one point I received an offer with an expiration date before I had finished my interviews. This caused me so much stress that I developed migraines and stomach aches. Interviewing after having an offer on the table felt like I was cheating, but I didn’t know on whom (the place who had given me an offer or the place where I was at). In the end, I decided to be very honest to everyone and I asked (and got) an extension on the deadline for my offer until all my interviews were finalized. I also informed everyone immediately after making my final decision, even if the universities had not made their final decisions.

13. You don’t need multiple offers to negotiate.

Ask for what you will need in order to be successful. Ask for a salary based on available salaries from similar institutions (public universities post their salaries) or recent hires. It’s more expensive for you to have a start-up that is too small to be successful, or for you to leave for a position with a better salary, than to provide you with the resources to run a successful lab and be happy in the place you’ll live in. As aside note: some universities require competing offers to negotiate, but most don’t.

14. It’s actually fun.

Aside from being an emotional roller coaster and an incredibly exhausting process – the in-person interviews were some of the most fun days I have had, ever. I loved talking about science for whole days and getting to eat in nice restaurants. I have received so much valuable feedback and input on my future research plans. I am inspired by how some departments are run and by many incredible scientists. I will keep many warm memories from this season. I hope you will too!

Image by Fakhruddin Memon from Pixabay

About the author:

Meike van der Heijden will start her lab at Virginia Tech in the School of Neuroscience and Fralin Biomedical Research Institute in January 2024. Her work focuses on studying the development of cerebellar function in health and disease. Her goal is to be able to prevent, predict, and reverse pediatric movement disorders, like ataxia and dystonia, and autism spectrum disorder resulting from cerebellar perturbations during the developmental period. Connect with Meike on Twitter or LinkedIn.

About ecrLife:

We welcome comments, questions and feedback. Please contact us at ecrlife [dot] editors [at] gmail [dot] com.

Would you like to share your own story, insight or opinion? Pitch us here.

Follow us on Twitter or LinkedIn to stay up to speed with our latest news and blog post releases.