Most academic jobs come with flexible working hours which can be advantageous when researchers attempt to balance the competing obligations in their lives. Yet, when you walk into any lab, it is hard to spot an early career researcher (ECR) who only works during the hours they are paid for. What you mostly see is graduate students having dinner between experiments, postdocs going to work on weekends and PIs writing grants on their holidays. Academic culture has normalized overworking, sometimes at the expense of a social life, and of great concern, sometimes at the expense of researchers’ health and well-being. Increasing reports of mental health problems in academia starting as early as graduate school are linked to declining work-life balance, which is seen as one of the main contributors to stress. Sparing time for one’s self, family and friends is necessary for keeping a healthy, working body and mind and can improve your performance at work. However, due to the pressures, competition and increased demands, many researchers follow unwritten rules seeing a tipped work-life balance as the way to a successful career. But is it the only way?

Successful strategies need to be personalized and dynamic, while acknowledging that we work in a system and culture that place constraints on our ability to manage work-life balance as individuals.

As part of the Mentoring & Leadership Initiative of the 2019-2020 eLife Ambassador programme, we aimed to better understand the reasons behind work-life imbalance among ECRs to work towards solutions. We conducted a small survey in October 2019, asking respondents to share information about their own routines and experiences. The survey included multiple choice and open-ended questions where respondents could share their advice and opinion about attaining work-life balance. In total, fifty responses were collected from ECRs with different backgrounds, with most responses from PhD and postdoc stage researchers working in Europe and the United States. While our survey is somewhat limited due to the sample size, we were able to gain some insight and work towards building practical advice for individual researchers.

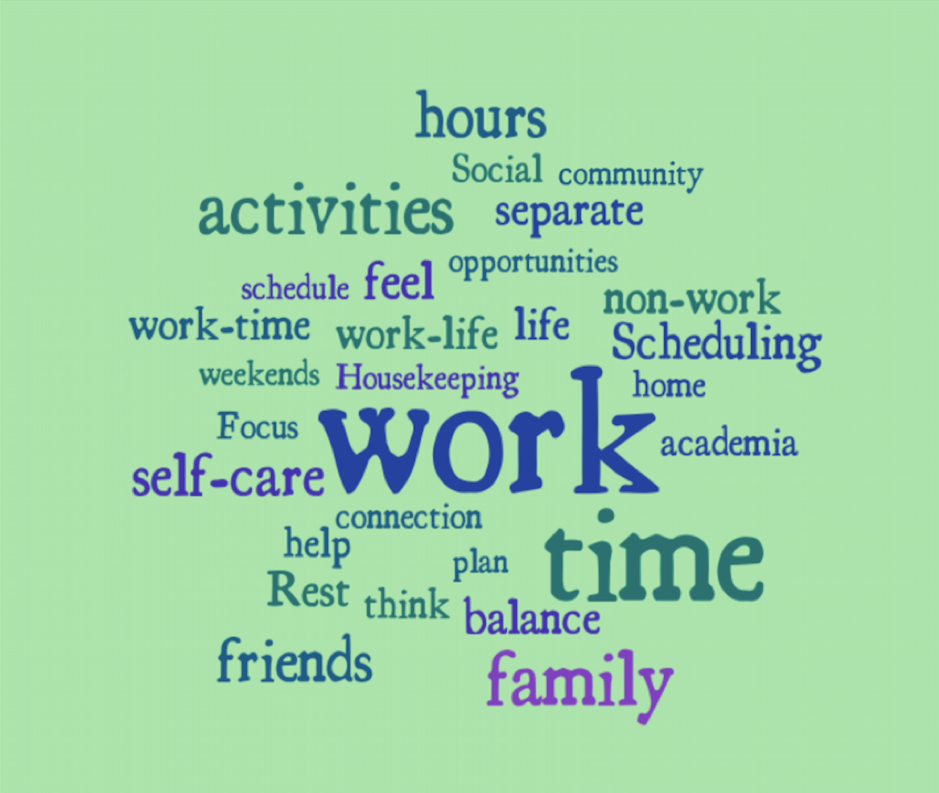

Nearly 70 percent of respondents, including those earlier and later in their career, mentioned that they struggled with work-life balance, while a further 8 percent suggested that they sometimes found striking a balance challenging (Figure 1). Looking at working routines and hours, we saw around 60 percent of our respondents worked 8 to 10 hours per day, and more than a quarter of respondents worked 10 to 12 hours per day (Figure 1), which is significantly longer than the normal working hours of academic employment contracts (40 hours a week for full time researchers in most countries). This generally aligns with recent large-scale surveys of graduate students and academics across a range of career stages that reflect a widespread culture of overwork and presenteeism. In another large scale survey, around 25 percent of respondents indicated that they typically worked between 6 to 8 hours on weekends. Nearly 80 percent of our respondents mentioned that they have worked on weekends, most indicating that they did so when deadlines approached, while some from the remaining 20 percent said they made changes to intentionally keep their weekends work-free as they reached later stages in their careers or when they became parents. When asking respondents who struggle with balance, “What do you feel like you do not have time for?”, half indicated they lacked time for rest and self-care, and/or relationships (e.g. spending time with partners, family and friends), while about a third found it difficult to fit in time for other activities (e.g. sports and hobbies), and about 20 percent struggled to keep up with general household chores (Figure 2). Even after realizing all these costs, why do many ECRs continue to overwork?

While researchers are passionate about their work, the excitement of doing research does not seem to be the driving factor behind these overworked hours. ECRs seem to suffer from anxiety around not working hard enough and progressing at a slower rate (self-declared/assessed) than their peers when they take time off. About a third of our respondents said they felt they didn’t have enough time for work and felt under pressure to be doing more. Out of all the respondents, only one attributed this to pressure from their supervisor. Comments from many respondents suggest that the race to publish and a lack of positions and funding, which are also identified by scientists as the biggest challenges to their career progression, are the drivers behind work-life imbalance. On the other hand, achieving a sense of work-life balance is dependent upon individual circumstances and values that can change over time. What works for one may not work for the other, and a solution that works now might not be particularly effective in the future. Here lies the major challenge when trying to give general advice about achieving balance - successful strategies need to be personalized and dynamic, while acknowledging that we work in a system and culture that place constraints on our ability to manage work-life balance as individuals. With this in mind, we need to tackle these issues at both personal and institutional levels.

Overworking does not equal productivity and learning how to effectively manage your time and focus while at work is critical.

To the question, “What advice would you give to your younger self?”, many replied they would have reduced overworking and would instead try to work more efficiently by planning their schedule better. Overworking does not equal productivity and learning how to effectively manage your time and focus while at work is critical. According to our survey results, effective planning and time management are key to keeping work-life balance for individuals. Specifically, many researchers purposely set boundaries, clearly defining working hours to impose temporal boundaries, as well as not taking work home to impose spatial boundaries. It is important to remember that this survey was conducted pre-COVID-19, before many of us around the world started working almost exclusively from home. It is also worth mentioning that the flexibility of working away from the office, at home or elsewhere, can be useful in maintaining balance, provided your use of time is well planned. If you are working from home, it is a good idea to set up a dedicated working space if possible, which can help keep work separate from home life. Another common practice from the survey was to schedule specific times for social activities and exercise, by arranging ahead of time with people or signing up to regular classes/courses, which made the plans harder to cancel. Although COVID-19 restrictions make this more challenging, it is still possible to schedule times to exercise at home and arrange regular activities online, which are even more important in these days when we need to find creative ways to keep social interactions. Other important suggestions from participants in the survey included learning to say no when required, and sharing and delegating responsibilities to make work assignments more manageable.

If you are working from home, it is a good idea to set up a dedicated working space if possible, which can help keep work separate from home life.

It is vital to realize that personal changes alone are not enough to solve the work-life balance issues in the research sector. As mentioned, researchers of all levels seem to enforce overworking on themselves and attribute this trait to the pressures of publishing and securing funding. In the long run, our respondents commented on the need for increased science funding, creating more permanent research positions, and increasing the length of contracts and fellowships. Change can be brought about by a shift in research culture, where a top-down approach is necessary. Part of the solution starts with PIs encouraging the students and postdocs in their groups to keep a healthy lifestyle, and setting examples themselves. Spreading awareness about the importance of work-life balance, promoting good practices, providing management and mentorship training, and employee-friendly policies at institutes are also needed. As one respondent captured it nicely: “Doing research is a marathon, not a sprint.” Ultimately, for the benefit of researchers and the important work that they do, both individuals and institutions need to make health and well-being a priority.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarvenaz Sarabipour and Adriana Bankston for discussions, advice and feedback. We are extremely grateful to all the survey participants for making the time to share their opinions.

Ethics Statement

As the survey informed participants about collection and publication of anonymized answers, and posed low risk for the participants, it was given an exemption for IRB review by IST Austria Ethics Committee.

About the authors: Feyza is a PhD student at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria. She studies cell-cell adhesion using zebrafish embryos. Michael is a postdoc at Scion in New Zealand, where he studies the reproductive biology and life cycles of forest pathogens. Connect with Feyza and Michael via Twitter or email (farslan@ist.ac.at ; michael.bartlett@scionresearch.com ).