Many scientists who identify as trans suffer from discrimination. Nearly 50% of trans people in physics have experienced exclusionary behavior in their workplace, according to a 2016 report from the American Physics Society. In the UK, 20% of trans people in the physical sciences have considered leaving their workplace because of a hostile climate or discrimination. A trans(gender) person is someone whose gender identity does not match the sex they were assigned at birth. I am a trans scientist and I think the scientific community needs to become much more welcoming to scientists like me.

As a trans person in science, I have to make choices on a daily basis that cis (non-trans) people do not have to consider. Some might be small: an absence of gender-neutral toilets in my building means that I sometimes have to decide between walking through the rain to the next building with such facilities, or going into a gendered toilet that I don’t feel comfortable in. Other issues, such as misgendering and overt transphobia by colleagues and prominent lecturers within my university, are much bigger. For example, on the same day I hosted a trans speaker for our LGBTSTEM day event, a prominent professor at my university published a transphobic article. This not only makes me feel unsafe, but also makes me worry about inviting trans speakers in the future. In these cases, I have to decide whether to speak up which could 'out' me and make me a target for transphobia, or to stay quiet and allow the transphobia to continue. So far, my tactic has been to avoid the people I know are transphobic, but this is not always possible at my university's small community.

My science is also affected by the decisions I have to make. When I see a conference that's relevant to my work, I first have to check whether the country is safe for trans people. I was recently rejected from a summer school in the UK, but was encouraged to apply for the next iteration. Next year's iteration will be held in Russia though, a country I would not feel safe in. Apart from the location, I need to consider whether I can wear a badge displaying my pronouns, or bear being misgendered for the duration of the conference. I am also aware of my privilege as a white, able-bodied person. I cannot imagine how complex these decisions become for minority trans people.

For me, one underlying cause of these problems is a lack of visible role models for scientists who identify as trans. Seeing a renowned trans scientist would not only make me feel confident of one day becoming a principal investigator myself, but it would also show cis people that there is a place for trans people in science. My personal role model is Ben Barres - a renowned neuroscientist and also the first trans scientist elected into the National Academy of Sciences. He was scientifically accomplished, an active mentor and an advocate for trans scientists. His prominence and advocacy have made it much easier for me to talk about the challenges I face.

However, increasing the number of role models for scientists who identify as trans is not trivial. We have to focus on increasing accommodation and creating a more inclusive research environment. To do this, we first need to know who is out there and what accommodations they need. Data that is currently unavailable.

Although the last few years have seen more data on LGBQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual and queer) scientists, trans people are not always specified in these data sets, and if they are, they often comprise a small subset. For example, a 2018 study showed that LGBQ men were less likely to stay in STEM, but the study did not include trans people. Although LGBQ and trans people share some obstacles, such as an increased risk of mental health problems, trans people face unique obstacles such as accessing gendered facilities. In order to make science a better place for trans people, we need research and more data.

In general, there is a lack of awareness of what it means to be trans, and of issues affecting people who identify as trans. This is especially true for non-binary people, those who do not fit our binary idea of gender. I think this is in part due to a lack of education. For example, my university has organised an optional trans awareness training, which is only attended by a very small group of people. As a consequence, most supervisors at my university have insufficient knowledge of trans issues to properly support their trans students and peers. In addition, institutions could play an important role in providing guidelines on trans issues, so that researchers have a clear idea of how to respond to these issues. For example, these could include guidelines on how to ask for gender identity when performing human studies, or how to organise a conference on campus so that it is trans inclusive.

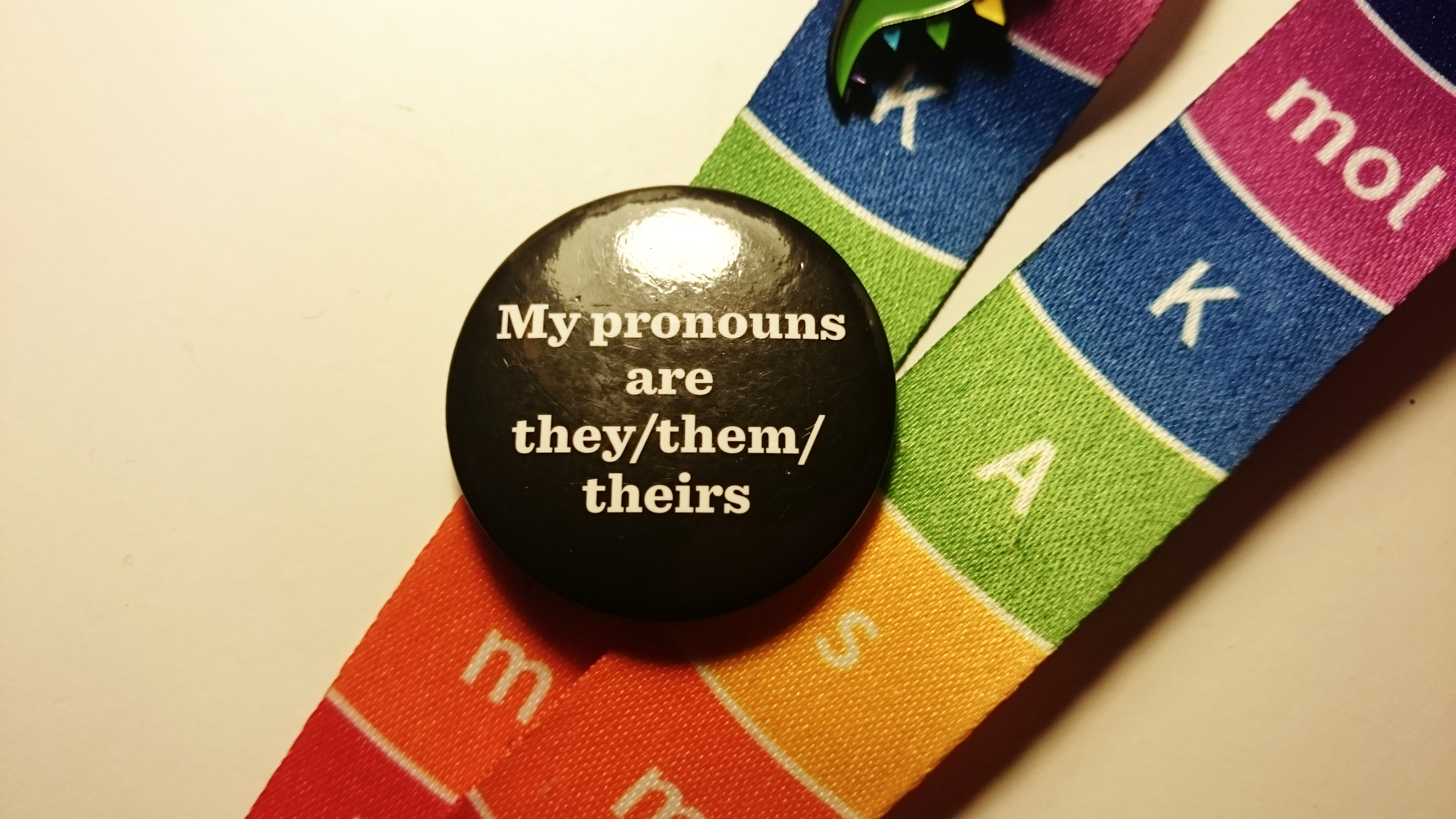

How can you help? An easy way for cis people to support trans people is to normalize the practice of giving your pronouns. You can do this in your email signature, on your opening slide for a talk, on your social media, or on your website. By using your pronouns frequently, you create a safe space for other people to share their pronouns. In addition, the more normalized this practice becomes, the less trans people out themselves by having their pronouns on their slides. For a trans person, outing themselves during a talk may cause peers to treat them differently, a possible reduction in job opportunity and possible other negative consequences that cis people are unlike to face when they put their pronouns on their slides. In addition, try to use gender-neutral pronouns (i.e. they and them), until you’ve verified what pronouns someone uses. That way you avoid accidentally misgendering someone.

Another great way you can help is by advocating for trans people when we are not in the room. For instance, you can advocate for gender-neutral toilets. When colleagues make transphobic comments, confront them and educate them why their comments can be hurtful.

Allies within my school have started adding their pronouns to their official emails, and this is now slowly spreading. I regularly get emails that contain people's pronouns, and every time this happens, my heart does a little dance. Although I have not yet been brave enough to add my own email signature with pronouns, I now know that I am surrounded by plenty of people who will support me, and perhaps soon I will find the courage.

About the Author:

Dori is a neuroscience PhD student at the University of Sussex in Brighton, UK. They study navigation in mice using virtual reality and two-photon imaging. At their university and beyond they advocate for more visibility and inclusion for LGBT+ scientists. You can find them on Twitter @DoriMatG.