Consider two female scientists, a heterosexual black woman and an LGBTQ white woman. Both scientists fall under the "woman" umbrella identity, but will have faced entirely different forms of discrimination in their lives and careers. This is because, while being a woman results in certain experiences of discrimination, being a black woman versus an LGBTQ woman results in distinct forms of discrimination. Now, let’s imagine that both women are applying to faculty jobs and are being considered at a university that has hired black men or LGBTQ men in the past and that neither woman was hired due to bias against their identity. The university argues that they did not discriminate against either woman, since they had previously hired black or LGBTQ male faculty members. The key difference here is that these women would have been discriminated based on the combination of two identities: being female AND being black or LGBTQ. Although intersectional discrimination in the US is illegal according to two different laws, people who file intersectional claims under both laws are less likely to win their case compared to those who file under just one law.

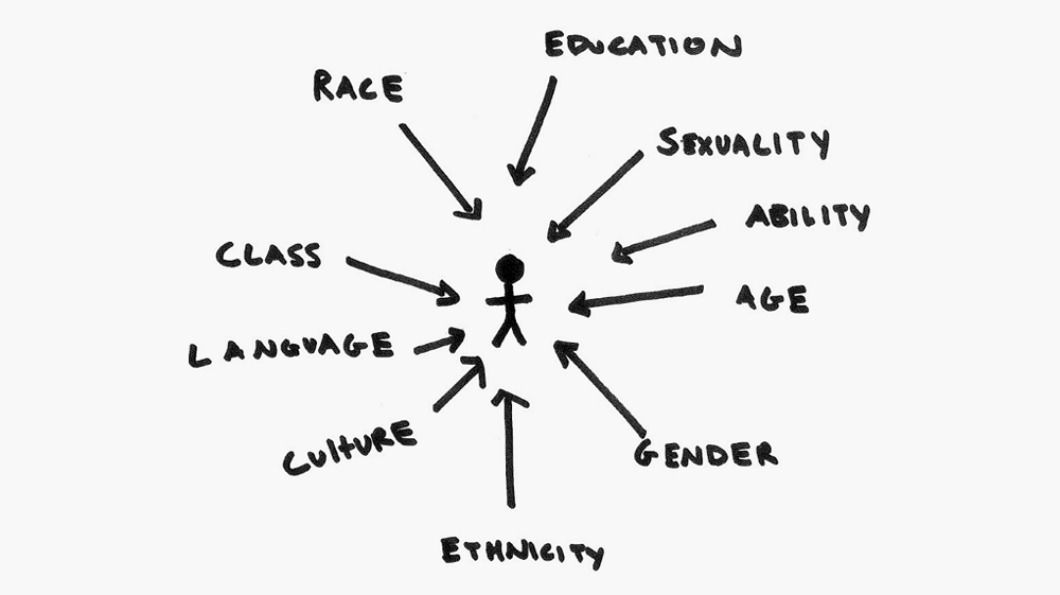

Intersectionality is a framework that helps us navigate through the combination of factors that shape individual experiences of discrimination. The term, popularized by American lawyer and civil rights advocate, Kimberlé Crenshaw, in the early 1990s, describes a concept of feminism that represents women of color, unlike early feminism that was dominated by heterosexual, middle-class, white women. More broadly, intersectionality is a concept that draws attention to how one's identity combines multiple elements, and how discrimination is often subversively practiced against the combination of elements that make up these identities rather than any single element. Going back to our example: the university may not discriminate against black people, women, or LGBTQ people in their hiring, but rather against the combination of two or more of these identity elements.

Women and minorities are still underrepresented at the faculty level, and if younger students with such identities fail to see scientists like themselves, they will likely feel unwelcome in the scientific community. How are we supposed to then inspire them to pursue science? Although we have made some headway in fostering a more diverse scientific community in the last decade, we still have a lot to accomplish before academia becomes a balanced and inclusive environment. Recognizing intersectionality in science in the way we hire, mentor, and collaborate is an essential step towards achieving this community.

As scientists, we share a common goal in the pursuit of knowledge, but we often work in multicultural environments, and our experiences in and out of the lab are profoundly shaped by our identities. There is no doubt that your identity and the way you are treated have had large impacts on your sense of belonging in the scientific community. If we ignore the compounding effects of our identities on our roles as academics and scientists, we potentially exclude people from the scientific community by not fostering an inclusive environment.

As scientists wanting to support our claims with data, we would like to highlight a study that shows the benefits of promoting diversity in academic research. After analyzing 9 million papers written by over 6 million scientists, AlShebli, Rahwan, and Woon showed that working with an ethnically diverse group of scientists correlates with a higher impact of the work (quantified by journal impact factor). While the authors did not take an intersectional approach and studied identities individually, these data clearly demonstrate that working in diverse teams leads to higher success and show that diversity in science is not only important for the well-being of scientists, but also for science itself.

Currently, many scholars, academics, and industries treat diversity as a check box: you hired a person of a particular identity, so you have fulfilled your inclusion requirement. Focusing on identifying underrepresented groups and increasing their representation in science is important. But reducing a person to a checkbox only strengthens the feeling of underrepresented people to not belong in the scientific community. In contrast, recognizing that not everyone faces the same level of discrimination or privilege based on a singular aspect of one’s identity will improve how we hire faculty, post-docs, technicians; how we recruit (under)graduate students; how we train and mentor future scientists and how we work together to perform scientific research.

A fraction of universities require diversity statements explaining your experiences and commitment to inclusion, when applying for faculty positions. Several universities are even starting to use this to identify promising candidates prior to assessing their ability to lead a successful research team (see UC Berkeley, UC Davis, and Wisconsin-Madison). We strongly believe diversity statements should be standard for faculty-level hires, and should also be incorporated at the time of tenure decisions and hiring at other levels in academic settings.

As a graduate student, one of us (Ashley) had the opportunity to serve on the hiring committee for the UC Berkeley Life Sciences Cluster Hire in 2019. Over 800 applications across multiple departments were reduced to 120 based on the diversity statement alone, which omitted identifying information. Obviously every institution wants to hire the best scientists, but conducting the faculty search using diversity statements enriched for talented scientists that also care about diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I). Identifying such advocates is a crucial step in improving the climate of academia. These candidates are not being hired to mark a checkbox, nor are they being asked to go above and beyond to improve DE&I as their overall service load will be equal to that of existing faculty. Instead, we evaluated the candidate's potential holistically, considering teaching, mentorship, commitment to DE&I. In the future, intersectionality will become standard for all applicants within our department.

In addition to altering hiring practices, we need to reflect on how we mentor and retain all scientists. Each trainee will require tailored mentorship to foster their feeling of belonging and to enable them to become successful scientists. Trainees from underrepresented or marginalized groups have a harder time finding faculty role models who might have had experiences similar to their own. I (Sarah) do not fit the ideal role model for all those I have trained, but I strive to mentor trainees using individualized approaches. Here are some important things I have learned from training individuals from diverse backgrounds:

- Avoid forcing a trainee to be a spokesperson for their gender, race, age group, or other identity. While their perspectives are wanted, allow them to offer their thoughts freely and remember that each represents an individual point of view. Each identity group may face different issues and experiences, but not all trainees from that group will share the same thoughts and perspectives.

- Direct trainees to additional programs and centers across the institute that may provide them with a community whose interests intersect with their own.

- Identify trainees who find it challenging to take active roles in academic or social settings and take initiative to include them.

- Ask your trainee about their research interests, hobbies, and activities outside of their program and if possible, introduce your trainee to others with complementary interests.

- Set ground rules regarding interactions between lab-mates with all members of your lab and explain how your expectations of cooperative support will advance the scientific goals of the lab.

- Be open to hearing trainees’ experiences and perspectives.

Focusing on how to appropriately mentor every individual is essential for their success, and for the success of scientific research. Intersectional practices provide a framework for individualized training, but also highlight the complexity of inclusion. One box does not fit most scientists and therefore refining our hiring, mentoring, reviewing, funding, and other scientific practices is required to appropriately promote the most productive and impactful research.

About the Authors:

Sarah Hainer is an Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh in the Department of Biological Sciences studying how chromatin and gene expression regulate cell fate. Follow her on Twitter @HainerLab.

Ashley Albright is a PhD candidate at UC Berkeley in the Molecular & Cell Biology Department studying enhancer function. Follow her on Twitter @aralbright93.

*Banner image credit: International Women's Development Agency