Dramatic declines in the output of some society journals over the last five years has led to a shift of power in publishing, raising tough questions for scientific communities

”Peer-reviewed journals… and publications with latest info on techniques and trends in the field” are the most valued aspects of scientific societies according to a 2014 survey by Wiley. Society publications, run by academics, have traditionally been the means by which scientists can act as curators and policy makers within their community, but with current trends, these roles will be increasingly be taken out of their hands. Further, as the activities of many societies are underpinned by income from their journals and conferences, a decline in proceeds is likely to have an affect on their wider activities aimed at community support.

Here I wanted to discuss what impact the last 5 years of competition in scholarly publishing has had on society journals, potential causes and implications for the future.

Society journals – in trouble?

For the sake of demonstration I pulled data about journals categorised under ‘Microbiology’ from the web of science. In 2012, three of the top five journals by output were published by the American Society of Microbiology (ASM) (Table 1), highlighting the central role of ASM in curating and publishing microbiology research. Five years later, none of the ASM journals were in the top five by volume, and only one in the top 10. The combined number of publications by the five major ASM journals had slumped by over 40%.

| Journal |

# Rank of journal by output |

|

|

2012 |

2018 |

|

| Journal of Bacteriology |

2 |

>20 |

| Applied and Environmental Microbiology |

3 |

14 |

| Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy |

4 |

6 |

| Journal of Clinical Microbiology |

7 |

>20 |

| mBio |

>20 |

18 |

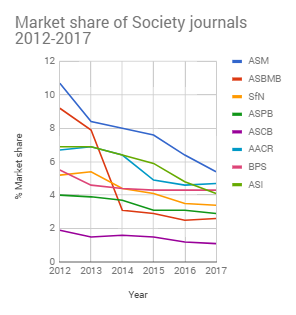

This is not an isolated phenomenon, for example, the Society for Neuroscience journals have seen an ~30% decrease in output and The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (ASBMB) titles experienced ~55% drop in publications over the same time period.

Not all societies have been so badly affected, out of ones analysed here ASCB, ASPB and BPS have seen only slight reductions in overall numbers of articles published, and AACR has increased output. But all have seen their market share decrease (Figure 1). Understanding the needs of their members (and potential members) is key to the success of scientific societies, so what may be going on?

Sound Science and the digital publishing revolution

The precise conditions each society journal is facing depends on the subject area, and is affected by a range of issues including competition and journal policies. However, there have been a couple of big developments that may be having an impact.

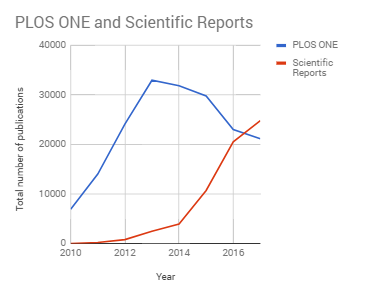

For example, the launch of PLOS ONE, the first ‘megajournal’, was revolutionary. It vowed to accept papers based on soundness of science rather than ‘impact’. As an online publication, unrestricted by physical limits of a paper bound journal, it embraced the ability to accept vast numbers of articles, and to make all content open-access.

The experiment was incredibly successful, with the journal becoming the world’s largest in 2010, reaching a maximum output of >30,000 papers a year in 2013. Scientists seized the opportunity to publish their work without the concern of perceived impact, without extensive delays and without requests for additional, unnecessary experiments.

PLOS ONE also demonstrated that expansion in scale afforded by electronic publishing can generate vast venues. As a result, commercial publishers launched their own ‘sound science’ platforms, including Nature Publishing Group (NPG)’s Scientific Reports, which overtook PLOS ONE as the largest journal in 2017.

Taken together, this suggests:

- ‘Sound science’ has become widely acceptable as a criteria for publication

- In many instances, scientists want to get (at least some) of their work published as quickly as possible, without being held up by reviewer reports asking for additional experiments and without concerns over perceived ‘impact’.

A quick analysis of a selection of societies reveals they have been slow to join the digital publishing revolution. Only six out of 11 analysed have at least one online only title, and only two have their own ‘sound-science’ platforms, in ASPB’s Plant Direct, and FEBS, FEBS-Open Bio .

| Society | Online only | Type | Relationship | Date Online Only |

| ASM | mBio | selective | flagship | 2010 |

| ASBMB | MCP | selective | specialist | n/a |

| SfN | eNeuro | selective | 2014 | |

| ASPB | Plant Direct | sound science | 2017 | |

| ASCB | MBoC | selective | flagship | 2007 |

| AACR | No | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| BPS | No | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| ASI | No | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| FASEB | No | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| FEBS | FEBS-Open Bio | sound science | open access | 2011 |

| FEMS | No | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Sound-science publication is here to stay, and an increasing number of researchers are opting for it. As things stand, in many disciplines, societies are not going to be the ones disseminating this type of research.

Capitalising on digital publishing

From one perspective, this may not be a problem, as society journals are often viewed as curators of some of the best work in a given specialism. However, with the number of publications growing each year this approach effectively shuns a position of influence over an increasing percentage of the scientific literature.

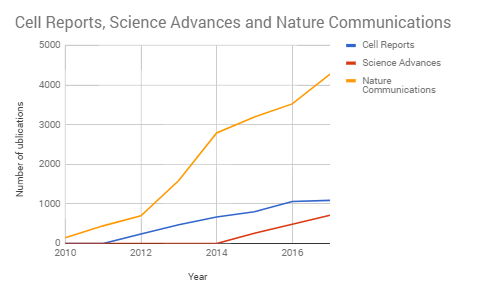

Further, there is an additional aspect to online publishing that commercial organisations have been very successful in implementing, and that society journals have not – publishing cascades. In the past decade several commericial publishers have set up selective online journals including Nature Communications (2010), Cell Reports (2012) and Science Advances (2014). These platforms accept articles that might not meet the requirements of their flagship publications or specialist titles, but are still perceived as ‘impactful’. Again, the success has been startling.

As a result, a handful of publishers can now offer an integrated hierarchy of titles catering to every level of scientific output, from groundbreaking work (e.g. Nature), leading specialist reports (e.g. Nature Genetics), impactful studies (e.g. Nature Communications) and incremental research and sound science (Scientific Reports). In doing so, publishers have solved a long standing problem for authors, allowing them to transfer their reviews and manuscripts (and reviews) between titles with comparative ease, so if they are rejected at one tier, they can move to the one below, theoretically reducing the pain of the publishing process. The benefit to the publisher is they can maintain high standards in top titles, while not rejecting potential customers.

The reasons for the success of cascades are authors want to avoid:

- Having to go through the review process multiple times

- Repeatedly filling out submission forms at different journals

There have been some efforts by societies to address these issues, such as the Neuroscience Peer Review Consortium, which allows transfer of reviews between journals, and the establishment of the Life Science Alliance – a cascade publication set up by EMBO Press, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press and Rockefeller University Press. But to be most effective it is likely to require integration of editorial systems, as with commercial titles, such that manuscripts can be easily transferred from one organisation to another.

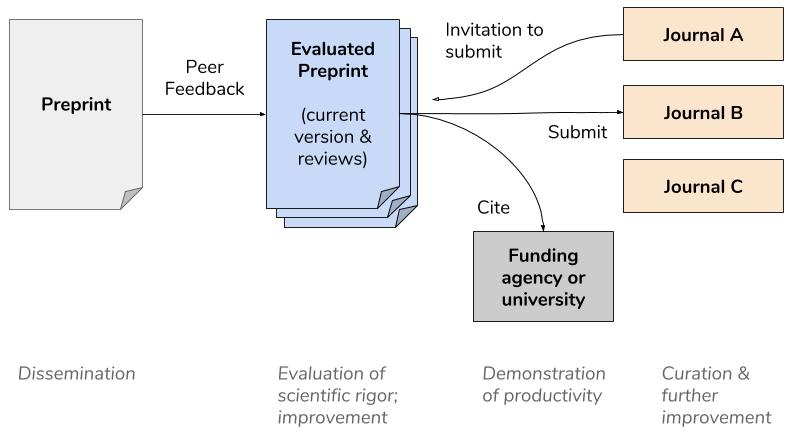

Other more radical alternatives to publishing cascades have also been suggested, such as ASAPBio’s Peer feedback, where preprints would be first openly reviewed then journals can invite authors to submit, or even splitting the publishing process, where all articles first are screened for soundness, accepted, then journals make an editorial decision to invite publication based on impact. But making the publication process painless for authors remains a challenging issue.

Other factors challenging society journals

Digital publishing has also reduced the importance of societies as a conduit for the latest research in their field. Gone are the days when academics waited for news in the mail, with scientists increasingly using search engines (such as pubmed and google scholar), email alerts (google, NCBI, scoop.it etc) and social media (e.g. Twitter) to keep up to date. Even the ability for researchers run special issues on niche topics, traditionally done through societies, is now an option at Frontiers.

Getting information directly from a specific journal may no longer always be the best way to stay informed. Indeed, there is even an increasing trend towards getting the latest advances directly from preprint servers such as BioRxiv, and it will be interesting to see if approaches such preLights or BioOverlay, which highlight recent preprints, will increase in importance over time.

How societies respond to these changes could have a bearing on their future success. One example of a society adapting to the new situation is my own society, The American Society for Plant Biology (ASPB), which has established an online community platform called Plantae. It includes sections such as ‘What are we reading this week’, podcasts, resources and networking opportunities. These efforts are well supported on social media through personal outreach to encourage engagement.

Concluding thoughts

There are many other factors involved here that I didn’t get round to mentioning, including the role of the impact factor in influencing scientists’ choices, the new regional communities being created by changes in scientific output, and the ways that people network online.

But, does all this matter? and should you care? These are open questions; it really depends on how important societies are to you. Does your society provide you with the networks and information you need to succeed? Is the increasing professionalisation of scientific publishing a good thing, that brings higher standards with the potential to reduce the workload of academics? Or is it a concern that scientists are losing control over publishing in their own disciplines?

To offer my two cents, I would argue societies would be best placed embracing digital open access and work hard to implement their own journal cascades. Further, to ensure the next generation of scientists remain as loyal and committed as the last, it would be beneficial to increase the voice of ECRs within society decision making and provide opportunities for ECR development, such as positive approaches to the inclusion and training of diverse ECRs in the publishing process itself as reviewers or associate editors.

The international scientific community is changing rapidly; societies can still succeed based on their core strengths – publishing and providing a community, so long as they keep changing to reflect it.

[Disclaimer: I have previously worked for eLife as an editorial community manager and PLOS as a blog editor. I am currently affiliated to eLife as an ambassador and member of ASPB. All opinions expressed in this article are my own]